Introduction

Arabic undeniably holds a significant place among the world’s languages, a status that will persist for decades to come. It is one of the six official languages of the United Nations, alongside Mandarin Chinese, French, English, Spanish, and Russian. Ranking fifth in terms of native speakers—after Mandarin, Hindi, Spanish, and English—Arabic is spoken by over 300 million people. Furthermore, it is the official language in 23 countries that form the Arab League, with a growing population and GDP, alongside significant social, economic, and political changes, since the beginning of the last century.

Discussions about Arabic typically refer to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA)—the version that emerged in the Arab World in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and that is now taught in schools throughout the Arab World, and used in newspapers and magazines, and in televised news broadcasting.

This is the first of a series of articles I intend to publish that looks at various challenges facing Modern Standard Arabic and its speakers in the current era.

The motivation behind this and the articles to follow comes from over a decade of experience in crafting Arabic content within the IT domain in general, and the Information Security domain in particular, and the persistent challenges encountered along the way. Moreover, the motivation extends to addressing the inadequacies of current Automatic Translation and other Natural Language Processing (NLP) applications for Arabic relative to other major languages, the difficulties in generating gender-inclusive Arabic texts, and the challenges of User Interfaces formatting, and localization.

In this article I contest the widely held belief in the existence of a sole Modern Standard Arabic, arguing against its validity. This article explores the notion that the idea of a singular Modern Standard Arabic is a misconception, at least from the point of view of NLP. Instead, I hypothesize that there exist multiple Modern Standard Arabics that share grammar and a lot of vocabulary, but differ significantly in vocabulary and idiomatic expressions related to modernity, governance, science, technology, finance, and other areas.

As a native Arabic speaker, and as someone who received formal and university education in Arabic, and because of my current occupation in the field of Engineering and Machine Learning, I feel that I could provide a fresh insight into the challenges facing this language in the internet age, and in the age of Google Translate, Siri, Alexa, ChatGPT and LLMs and other great leaps in the field of NLP.

The Missing Glossary

Over the past decade, numerous international organizations and companies, eager to offer their applications and services to Arabic-speaking users, have reached out to me requesting an Arabic glossary of IT terms. In response, I typically provided two or three different glossaries, each offering varying translations for the same English terms. Unfortunately, this approach often failed to meet the expectations of these organizations, as they were anticipating a single, definitive glossary, or “The Glossary” to guide their translations.

The task of providing the Arabic glossary might sound simple and straightforward, but for reasons I will illustrate in the following paragraphs, it is a very complicated if not an impossible one.

This is a challenge that I dubbed “The missing glossary” challenge. By the missing glossary I mean the missing unique universal up-to-date glossary of IT terms in Modern Standard Arabic. Sadly, this issue is not limited to IT terminology, but one that affects fields such as science, technology, management, economy, and governance.

The problem here is that: There is no unique Modern Standard Arabic glossary that is up-to-date. Instead, there are several Modern Standard Arabic glossaries that are different from one country to another. Furthermore, glossaries addressing different yet related fields, like Telecommunication and IT, often differ even though they are published by the same publishing house in the same country in the same year. Finally, many of the available glossaries are outdated as the pace of deriving terms in Arabic has been slow, and sporadic.

In fact, I will try with this article to convince you that such a glossary is impossible because there is no unique Modern Standard Arabic but several Modern Standard Arabics.

The issue of the “missing glossary” has historical causes, which got intertwined with and exacerbated by socio-economy factors.

In the following paragraphs, I will discuss the historical context in which MSA was first developed and how it quickly diverged to the multitude of Modern Standard Arabics that we have today, then I will discuss the different root causes for the divergence and describe the dynamics that drove it at the beginning and is still driving it.

The Historical Context of MSA

The Ottman Empire Era

During most of the Ottoman Empire rule (mid-16th – early 20th century), the Ottoman Empire and with it the Arab world were isolated from socio-economy changes and the associated Science and Technology revolution taking place in Europe and the new world.

Sultan Salim III and the ruling elite realized the dangers and huge costs associated with lacking behind. Salim III was assassinated, in 1807, before he could do anything about it.

Across the Mediterranean, Mohammad Ali Pasha, the strong Ottoman governor of Egypt shared the views of Sultan Salim III, and began a series of steps to reinvent Egypt. For instance, he sent promising citizens to Europe, on an educational mission, to study, as soon as 1820. At that time, he hired European managers. He introduced industrial training to the Egyptian population and granted the French B. P. Enfantin permission to build technical schools modeled after the École Polytechnique de Paris.

Meanwhile, Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire at the time, eventually caught up, and Sultan Mahmud II kick-started a process, called “Tanzimat” to modernize the empire. The Tanzimat that started in 1839 and ended in 1876 brought significant changes to the social order, political, legal, and administration systems of the Empire. Among the introduced changes were the Ministry of Education creation in 1847, the establishment of the first modern universities, academies, and teacher schools in the Ottoman Empire in 1848, and the establishment of the Ottoman Academy of Sciences in 1851.

To put that in a global context, Cambridge University was founded in 1209, the Sorbonne in 1257 in Paris, and the University of Heidelberg in Germany was founded in 1386.

Al-Nahda

Mohammad Ali reforms in Egypt and the “Tanzimat” in the Levant sparked the Arabic renaissance, the “Nahda” in the late 19th and early 20th century, during which Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) emerged as the result of the translation movement and the rise of modern literature genres like plays, short stories, that gradually replaced the classical Arabic literature forms.

The translation movement was pioneered by Egypt’s Rifa’a al-Tahtawi رفاعة الطهطاوي (1801-1874), who supervised translations from French to Arabic on topics ranging from sociology and history to military technology. In the Levant, Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq أحمد فارس الشدياق (1806-1887), Butrus al-Bustani بطرس البستاني (1819-1883), and Ibrahim al-Yazaji إبراهيم اليازحي (1847-1906) contributed greatly to the movement and are also credited with the creation of Arabic journalism.

Francis Marrash فرنسيس مرّاش (1836-1874) introduced French romanticism to the Arab world. Jurji Zaydan جوري زيدان (1861-1914), is credited with developing the genre of historical fiction, and in 1913 Muhammad Husayn Haykal محمد حسنين هيكل (1888-1956) published “Zaynab” the first modern authentic Egyptian novel. Qustaki al-Himsi قسطاكي الحمصي (1858–1941), the writer from Aleppo is credited with having founded modern Arabic literary criticism.

1836 -1874 Alepp, (Ottoman) Syria

1861 Beirut, (Ottoman) Lebanon –

1914 Cairo, Egypt

1858 al-Mansoura, Egypt –

1941 Cairo, Egypt

1858 Aleppo, (Ottoman) Syria –

1941 Aleppo, (French Mandate) Syria

Poets, such as Ahmad Shawqi أحمد شوقي (1868-1932), broke away from the classical theme of Arabic poetry and started discussing modern themes. Soon enough, poets broke entirely with the classical form of “Qasida” and its limitations and “liberated” the Poem as Badr Shakir al-Sayyab بدر شاكر السياب (1926-1964), a pioneer in this reform would say.

The contributions of these and other pioneers kick-started a revolution in Arabic literature. MSA emerged as the result of the interaction of the “Nahda” movement and the revolution in Arabic literature.

Geopolitics

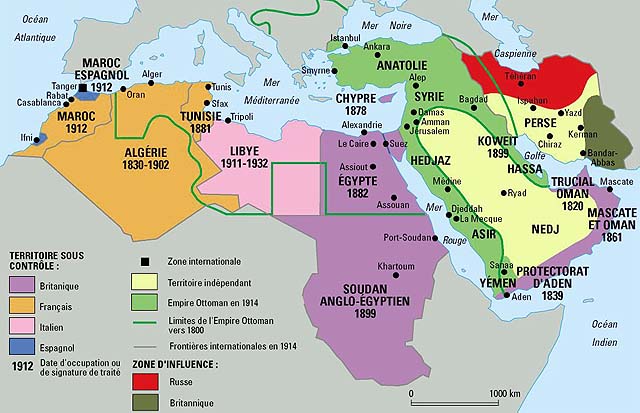

While the “Nahda” was taking shape, most of the Arab world was divided, occupied, or colonized by different imperial powers and largely underdeveloped.

Algeria was already under French colonial occupation since 1830. Tunisia was a French protectorate since 1881. Morocco was independent until 1912 when it became a French protectorate. Libya was under Italian rule since 1912. Egypt, which was still ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty, severed its ties with the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of World War I and became a protectorate of the British Empire. While Sudan was ruled as a crown colony since 1899.

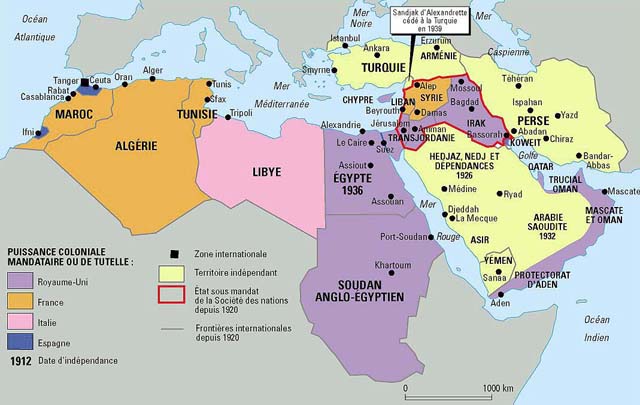

Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Levant were under direct Ottoman rule. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire with the end of World War I in 1918, the Arab world came to be controlled by the European colonial empires. The British Empire took control of Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq, and France controlled Lebanon, and Syria.

The Kingdom of Yemen seceded directly from the Ottoman Empire in 1918 and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which fragmented after 1918 was unified under Ibn Saud in 1932.

All occupied and colonised Arab territories gained their independence during or after World War II: the Republic of Lebanon in 1943, the Syrian Arab Republic and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1946, the Kingdom of Libya in 1951, the Kingdom of Egypt in 1952, the Kingdom of Morocco and Tunisia in 1956, the Republic of Iraq in 1958, the Somali Republic in 1960, Algeria in 1962, and the United Arab Emirates in 1971.

By: Philippe Rekacewicz, August 1992, Le Monde Diplomatique.

By: Philippe Rekacewicz, August 1992, Le Monde Diplomatique.

The result was a fragmented Arabic-speaking world. Fragmented politically, economically, and socially with big differences in governance models, legal frameworks, development levels, and with discrepancies in development priorities and national goals, focus, and aspirations.

Language, spoken or written, was not immune from this fragmentation.

Egypt and the Levant, versions of MSA were established as the language of governance while they co-existed with many local dialects and variations of these dialects that exist until this day. In Algeria, and Morocco and to a lesser extent in Tunisia, French was still the lingua franca.

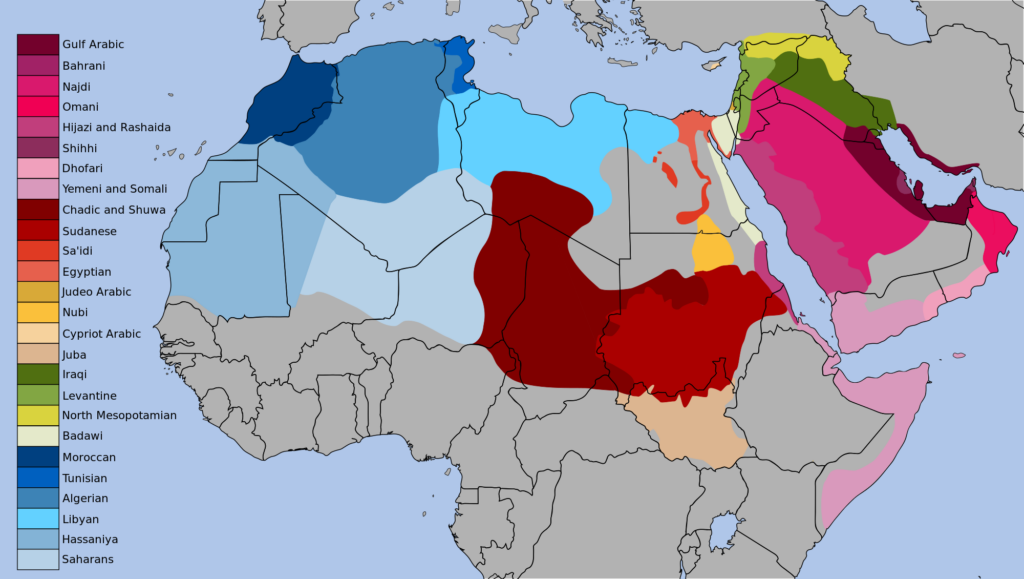

Although dialects are not the focus of this document, it is interesting to see a visualization of the dialects as it correlates to an extent with the fragmentation in MSA. A better-detailed map is available on Wikipedia.

The Many Arabic Academies

During the phase of national state building, countries that chose Arabic as the language of governance were facing a rather practical problem, as the need for Arabic terminology necessary for governance and for the day-to-day political and economic life was growing day by day. Each one of these countries, independently taking on the challenges of establishing systems of governance, needed an organization or a body to come up with the correct Arabic terms especially those related to modern state, science, technology, modernity, trade, and business for which no Arabic translation existed, except maybe in the work of Arabic luminaries of Al-Nahda, which was by no means comprehensive or coherent. This called for the creation of Language Academies.

Language Academies are the institutions that regulate languages and publish prescriptive dictionaries, which officiate and prescribe the meaning of words and pronunciations.

Arabic Language Academies were created, independently in the mid-20th century, in the Arab world to be the regulatory bodies of language in their respective countries. The oldest is the Arab Academy in Damascus which was founded in 1919, followed by Jordan Academy of Arabic in 1924, and then the Arab Academy in Cairo in 1932. Currently, there are 15 independent Arabic language academies across the Arabic-speaking world.

| Language Academy Name | City | Country | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arab Academy of Damascus | Damascus | Syria | 1919 |

| Jordan Academy of Arabic | Amman | Jordan | 1924 |

| Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo | Cairo | Egypt | 1932 |

| Iraqi Academy of Sciences | Baghdad | Iraq | 1948 |

| Institute for Studies and Research on Arabization | Rabat | Morocco | 1962 |

| Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters, and Arts (Beït Al-Hikma) | Tunis | Tunisia | 1983 (1992) |

| Academy of the Arabic Language in Khartum | Khartum | Sudan | 1993 |

| Palestinian Academy of the Arabic Language | Ramallah | Palestine | 1994 |

| Supreme Council of the Arabic language in Algeria | Algiers | Algeria | 1996 |

| Mogadishu Institute of Languages | Mogadishu | Somalia | 1997 |

| Academy of the Arabic Language in Libya | Tripoli | Libya | 1999 |

| Academy of the Arabic Language in Israel | Haifa | Israel | 2007 |

| Lebanese Academy of Sciences | Koura District | Lebanon | 2007 |

| Arabic Language Academy in Sharjah | Sharjah | United Arab Emirates | 2016 |

| King Salman Global Academy for Arabic Language | Riyadh | Saudi Arabia | 2020 |

These language academies publish glossaries of new terminologies usually coined from Arabic roots or Arabicized from Latin or English.

The different regulatory and governance systems in different countries, different priorities, and differences in institutional development, political difficulties, lack of coordination among these academies, and other related factors led to fragmentation in the terminology used in each country.

These academies publish their work independently and rarely collaborate or coordinate, and as a direct result, there are up to 15 MSA dictionaries or glossaries published by the respective 15 language academies. They are all MSA glossaries, they often have different versions of the same English term, and at the same time, they are all correct in their countries.

Let’s contrast that with the situation of the Spanish language. Like Arabic, Spanish is the official language of 20 different countries. However, unlike Arabic, Spanish-speaking countries recognized this issue early on and established the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language in 1951 to coordinate Spanish standardization. No similar effort to standardize MSA has been successful, despite several attempts, such as the Union of Arabic Language Academies of 1971, which became obsolete in subsequent years, but still exists until this day, and the Arabization Coordination Bureau in Rabat مكتب تنسيق التعريب بالرباط, which is a program by the ALECSO A Tunis-based institution of the Arab League, and the more recent and more promising Al Arabiah Council مجلس اللغة العربية founded in 2008, and that is now a partner organization of UNESCO.

It might sound counterintuitive that the establishment of language academies not only contributed to the fragmentation of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) but cemented that fragmentation. The existence of several regulatory bodies for MSA that publish independent dictionaries or glossaries is another argument for the opinion that there are several MSAs rather than one MSA.

As mentioned above, there have been several attempts to bridge the divide, including the Union of Arabic Language Academies of 1971 and the Al Arabiah Council of 2008 which has much more potential but is facing an uphill struggle in the post-Internet Era. However, we must not forget success stories, the most successful of which is the effort made to create the Unified Medical Dictionary (UMD) that was published in 1973 by the Arab Doctors Union, and that has been maintained and supported by the WHO since the 3rd edition in 1983, under the WHO Global Arabic Programme that has been successfully keeping medical and public health terminologies unified across the Arab world.

Sadly not all sectors are as fortunate as public health.

With a multitude of Arabic Academies dedicated to standardizing Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and publishing glossaries that include Arabicized terms spanning various sectors, it’s intriguing to consider the reasons behind the inconsistencies observed in the terms proposed by these distinct institutions. One might question why there isn’t a unified approach leading to harmonious conclusions across these academic bodies. This question paves the way to a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to the divergence in MSAs, which will be the main subject of the following sections.

The Driving Forces

In the sections that follow, I will outline several key driving forces behind the divergence in versions of Modern Standard Arabic, which continue to exert influence today and are likely to further drive these versions apart unless efforts are undertaken to mitigate them. The factors detailed here do not represent an exhaustive list but are chosen to illustrate the historical development of Modern Standard Arabic. They are presented not in order of significance but in a sequence that mirrors the historical context of MSA.

Local Dialects

One source of the fragmentation in MSA is the effect local dialects have on local Arabic language academies. Dialects that are used in day-to-day business, at home, and in the workplace seeps into the official language.

We don’t have to dig deep to find the influence of local dialects on the version of MSA, for instance in the Levant (Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel/Palestine) and Iraq, local Arabic language academies adopted the use of the Levantine month names, derived from ancient Syriac calendar, which are different from the months names adopted by the academies in Egypt, Sudan and UAE and that are phonetically similar to the English month names.

| English | Levant, Iraq | Egypt, Sudan, UAE, etc. | Morocco, Libya | Algeria, Tunis | Arab League Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | كانون الثاني | يناير | يناير | جانفي | يناير/كانون الثاني |

| February | شباط | فبراير | فبراير | فيفري | فبراير/شباط |

| March | آذار | مارس | مارس | مارس | مارس/آذار |

| April | نيسان | أبريل | أبريل | أفريل | أبريل/نيسان |

| May | أيار | مايو | ماي | ماي | مايو/أيار |

| June | حزيران | يونيو | يونيو | جوان | يونيو/حزيران |

| July | تموز | يوليو | يوليوز | جويلية | يوليو/تموز |

| August | آب | أغسطس | غشت | أوت | أغسطس/آب |

| September | أيلول | سبتمبر | شتنبر | سبتمبر | سبتمبر/أيلول |

| October | تشرين الأول | أكتوبر | أكتوبر | أكتوبر | أكتوبر/تشرين الأول |

| November | تشرين الثاني | نوفمبر | نونبر | توفمبر | نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني |

| December | كانون الأول | ديسمبر | دجنبر | ديسمبر | ديسمبر/كانون الأول |

One surprising example, is the pronunciation of some Arabic letters such as ق and “ج”. In the Arabic Peninsula region, “ق” is pronounced phonetically as “g”, while in Egypt “ج” is pronounced as “g”, because of that, the Arabic version of the name “Google” is “قوقل” while in Egypt it is جوجل and in the Levant where there is no phonetic version of “g”, “Google” is written as “غوغل”. As a result, in official documents in Egypt “جوجل” is used, while “غوغل” is used in official documents in the Levant.

Another obvious example is the official names of fruits and other staples and consumer goods that reflect the local dialects in the respective countries in official documents such as import, export, and pricing regulations, contracts, accounting, etc. I discuss these points in more detail below as market dynamics play an important role that is worth shedding some light on besides the role local dialects play.

Additionally, local dialects are also a result of the historical context, especially, the many years of direct Ottoman rule of large parts of the Arabic-speaking world, and the European colonial heritage many Arabic countries especially in North Africa have experienced in the 19th and 20th centuries, a subject I will discuss next.

The Colonial Heritage

The divergence in the Arabic language across various Arabic-speaking countries can be significantly attributed to the colonial heritage, a factor more recent than the influence of local dialects which evolved over centuries. This discussion encompasses the late Ottoman Empire era, considering its similar impact on the language due to the dynamics it introduced.

The main dynamic related to the colonial era is its influence on governance, institutions, education systems, and the enduring financial and political relationships post-colonization.

Countries under different colonial powers have incorporated terms from the languages of their colonizers. For instance, English-speaking countries have integrated English terms into their dialects, maintaining the English phonetic form, while French-speaking countries have adopted French terms. The months’ names table illustrates that phenomenon clearly.

The impact of colonization extended beyond the realm of language, shaping local governance structures to mirror those of the colonizers. In Lebanon and Syria, for instance, the French system of governance was established, embedding French political and legal terminologies and idiomatic expressions into the Arabic language spoken there. Conversely, Jordan and Iraq saw the establishment of a governance model akin to the British system, which likewise influenced the development of Arabic vocabularies and idiomatic expressions related to governance in these countries.

Moreover, the legacy of colonialism has facilitated partnerships and cooperation with former colonial powers, leading to financial, cultural, and academic exchanges. These interactions, including trade, university student exchange, and scientific collaborations, have further influenced the Arabic language by introducing new terminology from these foreign languages.

Geopolitics and Alignment

The geopolitical landscape and alignment of Arabic-speaking countries also play a role in shaping the divergence of the Arabic language. As nations navigate their positions on the global stage, their political, economic, and military alliances significantly influence cultural exchanges and, by extension, linguistic evolution. The dynamics of that influence are very similar to those associated with the Colonial Heritage but are much softer.

For instance, in the 70s and 80s, during the Cold War, countries closely aligned with Western powers may experience an influx of Western terminology and concepts, integrating these elements into their version of Arabic. This phenomenon is not solely confined to vocabulary but extends to idiomatic expressions, technical terms, and even educational content, which are often adopted directly from the languages of their allies. Conversely, nations with stronger ties to the former Soviet Union gained a different set of new idiomatic expressions and technical terms.

In a more recent example, Syria encourages the learning of Russian as a second language, which will affect the linguistic landscape of Syria in the future.

Publish or Perish

In the last century, if not all, almost all fields of knowledge, such as basic sciences (mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, etc.), social sciences (sociology, economics, political sciences, etc.), and applied sciences (agriculture, engineering, medicine, etc.) witnessed an exponential rate of growth. This growth was accompanied by an exponential rate of inventions and a similar rate of coinage of new terms mostly in German in the first half of the 20th century and then in English until today. Arabic Language Academies that were already overloaded with the task of standardizing the terminologies of the last few centuries were facing an exponentially growing challenge.

The output of the academies could not grow at the same rate.

At the same time, the pressure on university professors, researchers, and technologists to publish research papers, books, curricula, and public news articles was very high, and it became even higher with the advent of radio and television. These professionals did not have the luxury of waiting for several years while the regulatory bodies finished their work and produced glossaries containing the terms they needed to publish. “Publish or perish” is the rule. So, instead of waiting, they simply coined the terms in Arabic to the best of their knowledge and used them in the work they published. This led to huge discrepancies in the terminologies used sometimes within the same University, or the same Faculty.

Eventually, the academies were forced to adopt some of the terminologies that had been in circulation for decades, which were different from country to country. Some academies resisted and derived terms more coherent with the Arabic language, but again not all academies agreed on the derivation. In all cases, the “publish or perish” dynamic led and is still leading to more fragmentation.

The Invisible Hand of the Market

During my latest trip to Tunisia in 2018, I could not help but notice that many verbs and nouns used in the day-to-day workings of the economy and the marketplace differ from those used in Syria, where I originally come from. Below is a short list for the Arabic speaker to contemplate.

| English | Tunisian (Maghreb) | Syrian (Levant) |

|---|---|---|

| Car rental | كِراء السيارات | تأجير السيارات |

| Roastery | حَمّاص | مَحمَصة |

| Highway | الطريق السيارة | الأوتوستراد |

| Butcher | المجزرة | اللحّام |

| Street | نهج | شارع |

| Hair Salon | قاعة حلاقة | صالون حلاقة |

| Bakery | مخبز | فرن |

| Nuts | فواكه جافّة | مكسّرات |

To an Arabic speaker from the Levant, like myself, the Tunisian terms are Arabic and sound familiar but at the same time sound made-up or invented.

They are comprehensible, they make sense, but at the same time seem foreign. It took me just a little bit of flexibility and some knowledge of the Tunisian historical context to adjust to the Tunisian terminology. But no Arabic speaker from Syria would use the Tunisian terms in a formal or colloquial text or conversation in Syria.

These Tunisian MSA terms do not exist in the Syrian MSA. It is clear that at some point in the past, MSA in Tunisia evolved differently than it did in Damascus. The theme these terms share is that they are all related to the marketplace and the economy. The market dynamics seem to have a big effect on the divergence we observe.

There is always pressure on governments to enact and adjust policies and regulations related to the marketplace. The marketplace is almost always ahead of politics. New products, new services, and new ideas proliferate in the marketplace before regulations are in place to address them. In the absence of the Language Academies’ output regarding the development, the government is often forced to adopt terms used in the marketplace or a refined version of those terms.

When Language Academies come up with a well-thought-out Arabic term, it is often the case that the ship has sailed. The official MSA terms were too foreign to the marketplace that the market just ignored them, and so, to avoid misunderstandings, laws and regulations got drafted using the colloquial marketplace terms again forcing the hands of the Arabic Academies.

“Television” is a good example of that dynamic. The market adopted “التلفزيون”, governments refined it “التلفاز”, Language Academies coined the term “الرائي”, which is actually not in use.

This marketplace dynamic happened independently in every country, the local dialect, the colonial heritage, and the model of governance, all played an important role in driving the terminology further apart.

The Information Revolution

The last driving force I wish to discuss is a consequence of the advances in computing and telecommunications that eventually led to the information revolution. Arabic Language Academies had to face the avalanche of new terminologies that came out of mathematics, science, and technology, and were buried under several layers of new concepts and ideas that they were ill-equipped to handle.

The information revolution has not only amplified all other driving forces discussed above, but also introduced a new driving force behind the divergence of Arabic.

In the early stages of this revolution, tech companies, well-positioned to compete internationally, began targeting the Arabic-speaking world. This region was experiencing rapid growth during the oil boom in the Gulf states and North Africa. Major software companies, including Microsoft and IBM, sought to localize their products to outpace the competition. These companies hired linguists and Arabic-speaking engineers to introduce Arabic equivalents to their terminologies without coordinating with Arabic Language Academies or among themselves. The resulting terminology differed from one company to the other, and was significantly different from terminologies Language Academies were rushing to create.

This is a dynamic similar to that of the marketplace, except that the market this time is in Seattle or Silicon Valley, and the terminology feels imposed rather than organic.

Over the ensuing years, there was pushback and a discussion between end users, the marketplace, academics, Language Academies, and companies, and gradually the terminology settled.

But again, it did not settle for a unique set of terminology. Hence the motivation of this article.

To illustrate the disparities, I am selecting a few examples from the most recent available glossaries published by the Language Academy in Egypt (2012) Damascus (2016, 2017) and two other glossaries the first published in 2016 by ALECSO and the other by Telecommunication and Digital Government Regulatory Authority of the UAE

| Source | The Computers Dictionary – 4th Edition published by the Arabic Language Academy in Cairo in 2012 | List of IT and Telecommunication Terms published by the Arabic Language Academy in Damascus in 2016 and 2017 respectively | Technical Terms Dictionary published by ALESCO in 2016 | ICT Dictionary published by Telecommunication and Digital Government Regulatory Authority of the UAE, updated 2023 |

| Computer | الحاسوب/الحاسب | الحاسوب | الحاسوب | الكمبيوتر |

| Wireless Local Area Networks | – | – | شبكات محلية لاسلكية | شبكات المنطقة المحلية اللاسلكية |

| Broadband Wireless Access | التَوصُّل اللاسلكي عريض النطاق | النَّفاذ اللاسلكي عريض النطاق | – | النفاذ اللاسلكي للنطاق العريض |

| Augmented reality | – | حقيقة واقعية مزيّدة | الواقع المزيّد | الواقع المعزّز |

| Virtual reality | الواقع الافتراضي | – | الواقع الافتراضي | الواقع افتراضي |

| Server | خادم | مُخدِّم | خادم | خادم |

| Hosting | استضافة | تَضييف | – | استضافة |

| Service Provider | موفِّر الخدمة | مزوّد خدمة | مقدّم الخدمة | مقدّم الخدمة |

| HTTP | البروتوكول التشعبي لنقل البيانات | بروتوكول نقل نصوص ترابطية | بُرُوتُوكُول نَقلِ النَّصِّ المتَشَعّب | – |

| Remote Access Service | – | خدمة النفاذ البعيد | خدمة ولوج بعديّ | – |

| Hashing | فهرسة دالّاتيّة | تَلْبيد | – | – |

For the record, companies, universities, and software developers had to tackle an extensive list of technical obstacles to support Arabic. From introducing Keyboard Layouts, localizing month names, right-to-left text alignment, Arabic diacritics, and punctuation, the Hindu–Arabic numerals, Right-to-left text alignment, Arabic Typography, the Arabic dual form, and much more. They have done a great job.

Despite that, serious issues related to Arabic in the IT sector still persist, mostly because nobody cares or knows where to begin to deal with them. Such as right-to-left alignment when mixing Arabic and English text, the dual form when localizing from English to Arabic, the many inflection rules, and much more. Cataloging these issues and suggesting solutions will be the subject of future articles I am hoping to publish.

Conclusion

Based on the points I illustrated above, I am arguing that, for all practical purposes, there is not one MSA language. Insetad, several MSAs co-exist. These MSAs have a lot in common. They share a common grammar, and most of the vocabulary base, but they differ significantly enough when it comes to idiomatic expressions, and vocabularies related to science and technology, to be considered different but closely related languages, at least from the point of view of Information Technology especially from the point of view of Natural Language Processing, Machine Learning, and Large Language Models. The presence of different Arabic Language Academies, the market influence, the “publish or perish” dynamics, as well as other factors, are forces driving and perpetuating the divergence.

The question of how languages evolved is a hard one. Predicting the future trends for MSA(s) is even harder. However, there are strong signs that the Arabic language is on the decline. The number of published books has dropped dramatically in the Arabic-speaking world in the past decade. The number of books translated into Arabic is still very low in comparison with other languages. The catastrophic security, political, social, and economic situations in the last two decades in Arabic-speaking hubs such as Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria as well as across the Arabic-speaking world, have been one of the factors for the observed decline.

Although the opinions presented above might be controversial, they should still be taken seriously when considering the training datasets for future LLMs that want to better support Arabic. They should also at least be present in the “back of the head” of software and services developers that wish to target the growing market in the Arabic-speaking world, and get an edge over the competition.

Further Reading:

- Elmgrab, Ramadan. (2016). The Creation of Terminology in Arabic. American International Journal of Contemporary Research. Vol. 6.

- Al Aqad, Mohammed H. (2018). Fever of Code-switching and Code-mixing between Arabic and English in School’s Classrooms. Translation Journal. April 2018 Issue.

- Hamed, Fawzi. (2016). Terminology variation and foreign language hegemony: The case of the Arabic-speaking North African countries. Translation Journal. July 2016 Issue.

- Abouzahr, Hossam.(2018). Standard Arabic is on the decline: Here’s what’s worrying about that. MENASource. Atlantic Council. May 2018 Issue.

- Diego Farias, Louis. (2021). Arabic Support in Early Computers Globalization Partners International.

- Madhany, al-H. N. (2004). Arabic Windows: Arabicizing Windows Applications to Read and Write Arabic. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, 38(1), 44–54.

- Chen, Raymond. (2012). A brief and also incomplete history of Windows localization. Microsoft. DevBlogs. (Accessed 2024).

Disclaimer: ChatGPT 4 was minimally used for Grammar and spell-checking.